Submitted by Jane Durkin on Wed, 28/07/2021 - 10:54

Artificial Intelligence (AI) is an increasingly central aspect of language science research encompassing many areas from digital humanities and corpus linguistics, NLP applications like speech recognition and chat bots, to the use of machine learning to model human cognition.

Cambridge University is a world-leading centre for language and AI research. In this series of interviews, we talk to researchers from across Cambridge about their work in this field.

Tamsin Blaxter is a research fellow in Linguistics at Gonville & Caius College, Cambridge.

Her research explores mechanisms of language change and linguistic and cultural diffusion.

She is particularly interested in new approaches to data collection and the use of computational tools to acquire and analyse larger and more spatially fine-grained datasets than previously possible.

Her work includes research with datasets as diverse as digitized medieval Norwegian manuscripts to data gathered from social media and mobile phone apps.

Her current fellowship is on the dynamics of linguistic diffusion in medieval and modern Norwegian, investigating what determines the pathways particular linguistic innovations take, and how human and physical geographical factors determine these pathways.

Tell me about your research

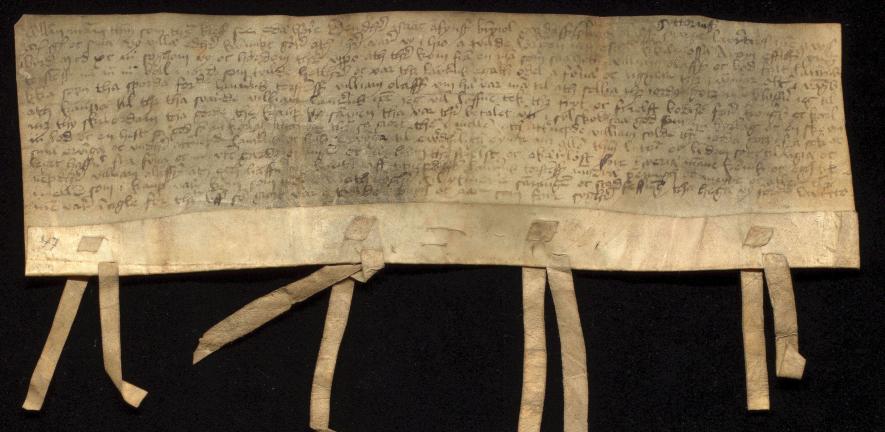

I think of my work with medieval Norwegian data as the central strand of my research.

In a way, it’s a data revolution in the humanities, the digitization of printed books, that allows me to do that work.

It’s not big data on the scale of what big data means to a lot of people, but it is bigger than anyone has worked with in medieval Norwegian before.

Why medieval Norwegian?

I was working on Scandinavian, but wanted to do dialects and there was this very good data set in medieval Norwegian.

There was this project – most of it happened between 1830 in 1920 – to transcribe and publish all medieval Norwegian documents in a book series. Then the Norwegian government, in a programme intended to increase computer literacy in the 1990’s, paid people to type up the books.

When I came to it at the beginning my PhD, I wrote scripts to transform it into useable formats, and spent two years identifying where all these documents were from.

At the end, I've got this big localized and spatially rich data set of documents spread over about 250 years. That's completely different from the resources anyone else had to work with before.

I came across one person’s master’s dissertation from the 1960s. They had read every document written in a single year in the Norwegian Middle Ages and marked a single feature. That had taken them a year. I can now do that for all the documents in a few hours. It really changes the game.

What is the Twitter project?

I have had two sets of collaborations in the last little while. One is what we call the Twitter project. The full title is ‘Investigating the diffusion of morphosyntactic innovations using social media’. That’s with David Willis (PI), Adrian Leemann and Deepthi Gopal.

Like my medieval Norwegian work, it’s driven by having these exciting new methods and datasets, and thinking what we can do with them.

We basically had a computer running for three years recording as close as we could get to all of Twitter in British English, Irish, Welsh, Turkish, Norwegian, Swedish and Danish – over 100 million tweets.

The advantage of Twitter is that it gives you masses of real usage text data.

This gives better resolution spatially on how language changes are happening, and that can enable us to answer questions about where they come from, why they happened. This time with modern instead of medieval languages, with a short time frame but a much bigger data set.

Tell me about your work with statistical physics models

The third major strand of my work in the last few years has been a series of collaborations with a physicist called James Burridge.

That's been really interesting. A very different way of working.

It’s about using the models of statistical physics as a starting point for trying to model language change.

The example we often give is statistical models for how magnetic metals change as they cool.

Normally we think of strong magnetic fields as being properties of solid metals. As a liquid cools, you can see the particles gradually align their magnetic fields. The magnetic fields of the particles get aligned so they have a collective magnetic field as a whole. They form regions, which get bigger until the whole space has a single region with this single alignment.

That’s our model for language change if you replace particles with humans.

What data have you used for this?

One dataset we've used a lot in with my work James is actually from the 1950’s, the Survey of English Dialects. It's the last time there was a national-scale survey to gather features of English and dialect variation.

Then for comparison, we used data from a project I was part of with Adrian Leemann and Dave Britain called the English Dialects App.

Adrian has led the trend of doing these gamified surveys in the linguistic sphere.

If we can't afford to do surveys which take 10 years and involve travelling all over the country the way they did in the 1950s, how do you get lots of people to take part in your survey. One possible answer is you don't tell them it’s a survey. You tell them it's a game.

The English Dialects App gives us a big data set of intuitions data for 26 questions, 25 of which were also in the Survey of English Dialects.

James and my most recent work, ‘Inferring the drivers of language change using spatial models’, has been to compare these two data sources as the beginning and end points, and to model the change that happened in between with our statistical physics models.

We're now trying to quantify the differences between what a pure spatial model can get, and what we actually see in real life, and using that to say we think other things have a big effect, like universal education, normative attitudes and what counts as ‘good English’.

What is the potential impact of this kind of research?

It's good to know this information from a social policy perspective, from the perspective of dialects being stigmatized and the push back in recent years against the idea that the standard is ‘morally better’. That fuller understanding could play into education policy, for example.

The models themselves if taken outside the sphere of dialect change, have other potential applications.

You might think about voting behaviour or other social processes with similar dynamics where people talk to their neighbours and imitate them, and there's some component of national scale normative through mass media.

That's something we're talking about taking forward.

What does the future hold?

I'm genuinely very excited by the explosion of work around social media.

There’s some great work you can do in understanding how people are actually behaving, how they are actually thinking and talking to each other, whether that be in linguistics, sociology, geography, contemporary history or other fields.

There's also the huge availability of audio data now. If we can find systematic ways of getting speech data with meaningful demographics from social media or crowdsourcing, maybe we can start to look at problems which no one has looked at an empirical way in linguistics.

How can we create more opportunities for interdisciplinary collaboration?

One of the things I see changing in my work, particularly within computational and corpus linguistics, is more collaboration. That is a positive direction. It enables us to work with bigger datasets and ask bigger questions. I wouldn't have been able to do the Twitter project on my own, for example.

The physics stuff is great. I don't think I would have predicted that. That has been incredibly productive and we should be doing more of that.

I’m also a poet and I write and read about queer theory in my spare time. There’s a lot of communication between ways of thinking about language, particularly historical language, that goes on in that space. So there's also interdisciplinarity in the artistic production side of my life.

SEE ALSO: Language & AI: an interview with Guy Emerson

Image credit for photo of medieval Norwegian charter from the corpus Tamsin works on: Ola Søndenå of Universitetsbiblioteket i Bergen