Submitted by Administrator on Mon, 13/08/2012 - 14:32

Recent research by scientists at the MRC-CBU has shown how subtitles not only aid our understanding of speech, but also provide the illusion that the speech is actually clearer.

We are all familiar with the huge benefit that television subtitles provide to hearing-impaired individuals, and their use in aiding comprehension of heavily-accented speech. Scientists have long debated how information gained from written text or other forms of non-speech context is exploited by our perceptual systems to help interpret noisy or ambiguous speech.

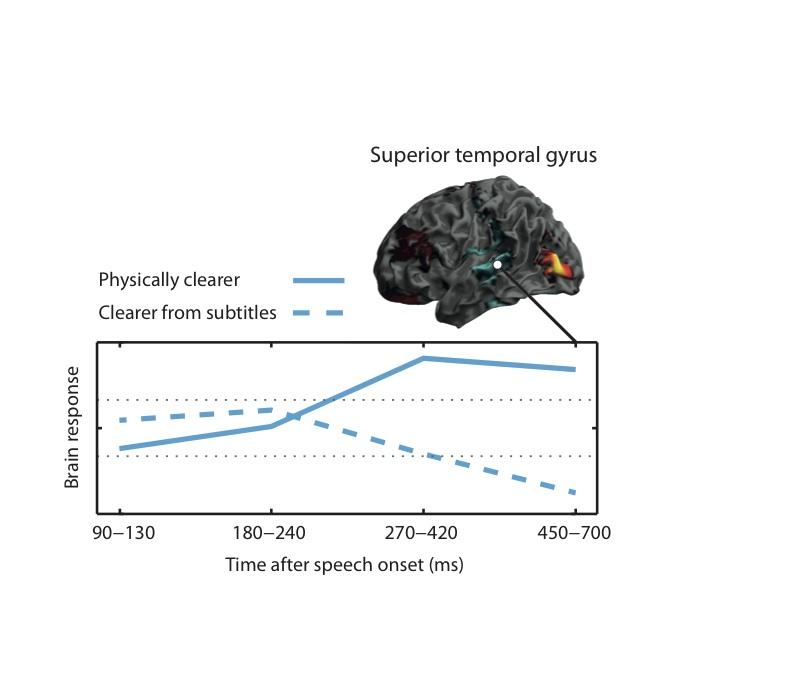

A new study published in the Journal of Neuroscience by Ediz Sohoglu, Jonathan Peelle, Bob Carlyon and Matt Davis used MEG imaging to show how the brain combines information from sounds with written text to make sense of noisy speech. Volunteers in the experiment heard recordings of spoken words that had been degraded using a signal-processing technique ('vocoding'), that mimics the way speech sounds to someone hearing with the aid of a cochlear implant. Words were degraded to a varying degree and listeners were asked to rate each word for how clear it sounded. Before being played each recording, volunteers read written words that sometimes matched the speech that they were about to hear. When the volunteers had this prior knowledge, they reported that the speech sounded clearer – exactly as if the speech were less noisy. However, auditory brain responses were opposite in these two cases: the MEG signal in the Superior Temporal Gyrus (a part of the brain involved in hearing) increased for speech that was physically clearer, but decreased for speech that was perceived as clearer because of previous subtitles (see diagram on this page). This shows that perceptual enhancement due to prior knowledge is consistent with a theory of brain function called 'predictive coding' whereby the brain constantly predicts the sounds that it expects to hear so that only unexpected sensory information ('prediction error') is processed in detail.This finding joins previous research in providing important insights into understanding the neural basis of uniquely human skills in speech perception, and helps explain how the provision of subtitles to hearing-impaired individuals changes their experience of speech.

You can read the paper in the Journal of Neuroscience here.

For a further article on related research at the MRC-CBU see Predicting sounds helps the brain to recognise words.