Submitted by Jane Durkin on Tue, 28/07/2020 - 17:34

For geographers, maps are everyday tools. I’m a historical linguist, and to me a map is a selection of locals’ speech presented in a visual manner. Here’s how I developed an appreciation for the zoomable maps available on the National Library of Scotland’s website and the University of Edinburgh’s Edina Digimap facility, and the Ordnance Survey Name Books available at ScotlandsPlaces.

In the introduction to Sunnyside: A Sociolinguistic History of British House Names (British Academy/OUP, 2020), I explain how I became aware that the ubiquitous house name ‘Sunnyside’ had an anterior history. I saw in an 1872 Post Office Directory that a large new Victorian villa in a place I knew rather well, Ealing Green, was named ‘Sunnyside’ and owned by a General.[1] This didn’t sound right. All the Sunnysides I’d ever come across were not posh, and the name was filed in the bin in my brain that stores “Treetops” and “Shirleydene” and “Enid Blyton”.[2]

So I sought out other Sunnysides, and I drew up biographies of their owners, finding that there weren’t any London Sunnysides until 1859, that in the 1860s they were still few; that early London Sunnysides were indeed large and grand, in leafy suburban locations, and owned by considerably rich, socially important, clubbable Nonconformists with Scottish connections. The first four London Sunnysides were owned by a Swedenborgian, a Sandemanian, the husband of a Wesleyan,[3] and a Plymouth Brother. Prior to that, Sunnysides around the country were owned by Quakers, who in the eighteenth century used the name ‘Sunnyside’ as an insider shibboleth.

Before ‘Sunnyside’ became taken up by Quakers the name was largely confined to specific parts of Scotland, Northumberland and Durham, and some of these North British historic Sunnysides are visible on maps. I hunted them down by various means, especially the Ordnance Survey Name Books. These are the notebooks of the mid-nineteenth-century Ordnance Survey officers who travelled around buttonholing locals, asking them what places were called and attempting to render the answer into something resembling a word, which wasn’t easy if they weren’t used to Scottish Gaelic. Sometimes alternatives were recorded, such as at East Auchenmade in Ayrshire where the ‘Various Modes of Spellings’ column also reports ‘Sunny Side of Auchenmade’. In the ‘General Observations’ column it says “Mr. Shanks the proprietor seems to care little which of the names be given he thinks either would do”. For a variationist such as myself this is good, because only one variant got printed on the map, and if it weren’t for the ‘Alternatives’ column we wouldn’t know of the others.[4]

I pinpointed the location of historic Sunnysides at https://maps.nls.uk, using the ‘Find by Place’ facility, and scrutinising individual Ordnance Survey sheets from top to bottom and side to side until I found the Sunnyside therein. I also hunted them down at https://maps.nls.uk/geo/roy, a digitisation of Roy’s Military Survey of Scotland of 1747-55; and at https://maps.nls.uk/atlas/thomson/index.html, John Thomson’s Atlas of Scotland of 1832, and in more modern times I checked them at http://geo.nls.uk/maps/gb1900/, amongst other surveys.[5] I also pinpointed Sunnysides at http://digimap.edina.ac.uk using the ‘Historic Roam’ function:

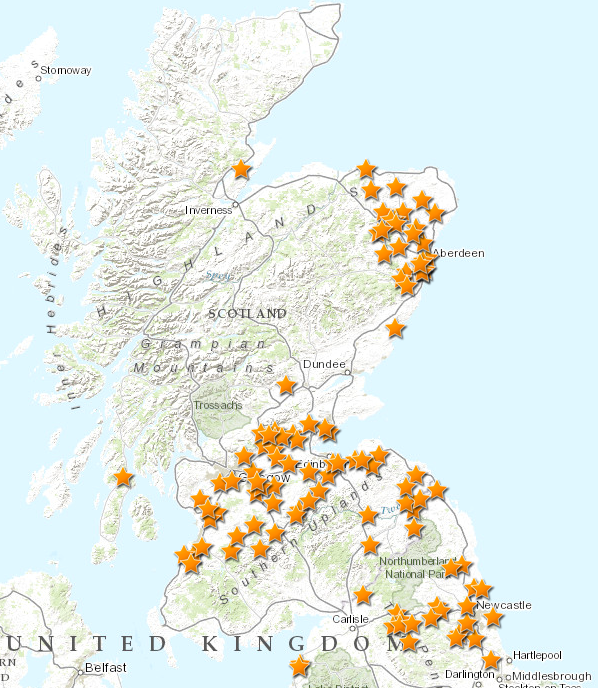

Map 1. Distribution of British steadings historically named Sunnyside, uncertain locations not included. Map produced in ArcGis. © Crown Copyright and Landmark Information Group Limited 2020. All rights reserved. (c.1583-1614 to 1922).

Splitting the landholding

The work of historical geographer Robert A. Dodgshon helped me make sense of the distribution. Map 1. is a map of fertile lands, where communities have subdivided territory according to a pre-feudal, solskifte method (as it is known in Norwegian), or vesying of the Sonysyde (as written in Older Scots in Peebles in 1555). Many Scottish placenames reveal former land-divisions, such as at Meickle Achinmed and Little Achinmed (Roy 1755), where the original descriptors are auchen, a Celtic word for a field, and med, which local inhabitants assumed was mead (of Old English etymology) also meaning ‘field’.[6] The antonymic pair meickle/little is Older Scots:

Map 2. Meickle Achinmed and Little Achinmed, Ayrshire: Roy Military Survey of Scotland, 1747-55. Reproduced with the permission of the National Library of Scotland.

So at Auchenmade we can posit an original holding referencing a field which was divided into two parts before 1755. By 1856 (the date of the survey for the the 1858 Ordnance Survey map) farms belonging to this naming unit were: Old Auchenmade, Little Auchenmade, East Auchenmade/Sunnyside of Auchenmade, North Auchenmade, South Auchenmade, Hacks of Auchenmade, Outer Muir of Auchenmade, and the Ordnance Survey Name Books reveal further variants Auchinmead Gemmill (alternative for Hacks);[7] Auchenmade Hillocks (alternative for Outer Muir); and the land tax rolls of 1812 reveal Auchinmead Mure and Auchinmead Barr, both the surnames of landholders.

Map 3. The agrarian unit at Auchenmade: Ayrshire, Sheet XII (includes: Stewarton; Kilwinning), survey date: 1856, publication date: 1858. Reproduced with the permission of the National Library of Scotland.

Continuities and innovations

Speakers expressed a parent-offspring relationship (meickle/little), the time-depth (old), the points of the compass (north/south/east), a distal relationship (the outer muir), their experience of the terrain (hillocks; Dictionary of the Scots Language Hack, n.2 ‘wild rocky stretch of moorland or moss’), the landholders (Gimmell, Mure, Barr), and the pre-compass way of dividing up land. These descriptors express speakers’ perceptions of their relationships and responsibilities to each other and to the fertile parts of their land across time and space.

Vesying (gathering together to observe and bear witness) a land division is expressed in Latin records such as the Register of the Great Seal of Scotland, where solarem dimidietatem equates to ‘sunny half’ (e.g. 1621: “solarem dimidietatem tertie parties terrarum de Cubakie, in parochial de Leucharis, vic. Fyiff”), and in Older Scots in documents such as the Records of the Sheriff Court of Aberdeenshire (e.g. 1574: “the sone third pleuch of the toun and landis of Wodlands in the Barony of Monycabok”). It required two constants: the time of day and the time of year. The interested parties moved in a sunwise (clockwise) direction to their selected spot at their selected time and observed where their shadows lay. Standing with their backs to their shadows, what they saw in front of them was the land to be witnessed and collectively orally recorded. Facing the sun at dawn on Lady Day is an infallible method (unless there’s a total white-out, in which case trying again next week will still work). Your shadow will always fall behind your back if you face the rising sun. The slope of the land is irrelevant, the ‘side’ in question is the shadow/non-shadow side of the vesyers themselves.

So Scottish relationship-placenames report land-division across the generations, and because Scotland was multilingual, these divisions were recorded in different languages. I conjecture that the prevalent Scottish name “Greens” was not English green but Gaelic grian, ‘sun’. And I noted that ‘Sunnyside of X’ (e.g. Sunnyside of Auchmunziel) and ‘Greens of X’ (e.g. Greens of Dunain) clustered, so I plotted them too:

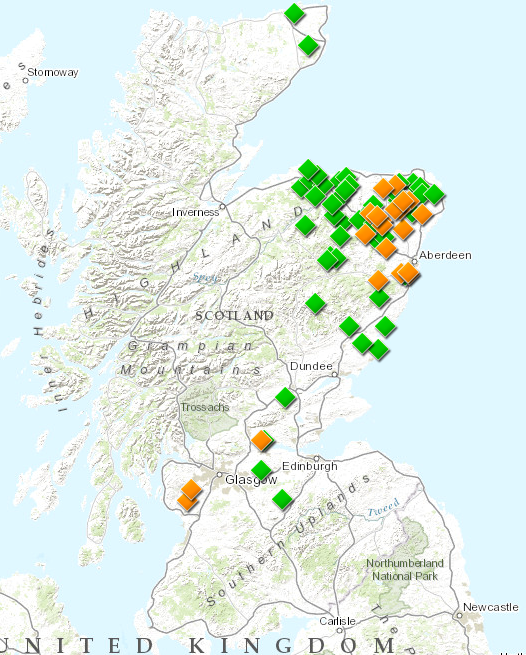

Map 4. Combined distribution of ‘Sunnyside of X’ (orange diamonds) and ‘Green(s of X’ (green diamonds). Map produced in ArcGis. © Crown Copyright and Landmark Information Group Limited 2020. All rights reserved. (c.1583-1614 to 1922).

Plotting revealed a similar distribution, and I accept Richard A. V. Cox’s observation that the ‘X of Y’ placename construction reflects underlying Old Norse syntax.

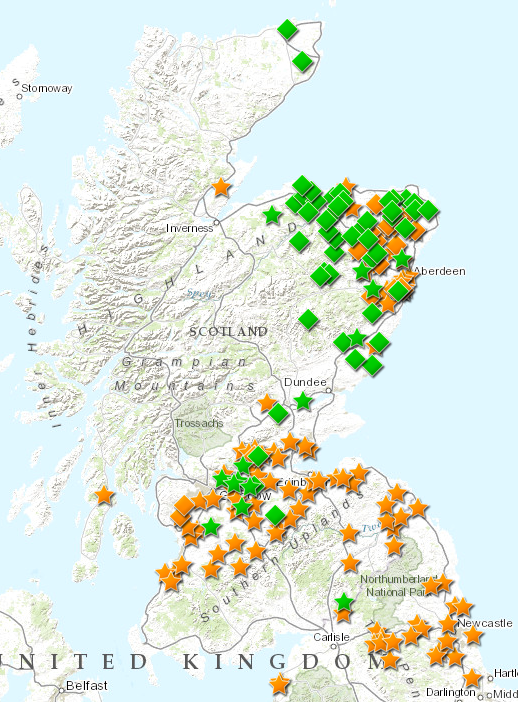

Map 5. Combined distribution of Sunnyside (orange stars), ‘Sunnyside of X’ (orange diamonds), Green(s) (green stars), and ‘Greens of X’ (green diamonds). Map produced in ArcGis. © Crown Copyright and Landmark Information Group Limited 2020. All rights reserved. (c.1583-1614 to 1922).

This set of relationships between Older Scots, Scottish Gaelic and Old Norse couldn’t have been easily identified without the ability to view and switch between the digitised historical maps at https://maps.nls.uk and http://digimap.edina.ac.uk. It enables a picture to emerge of continuity of speakers in place, their cultural practice and transfer of that culture from one language to another, followed in time by language loss as people abandoned the runrig system, forgot what the sunny side had once signified, and what grian had once meant.

Relevant Reading

Cox, Richard A. V. 2007. ‘The Norse element in Scottish place-names: syntax as a chronological marker.’ The Journal of Scottish Name Studies 1, 13-27.

Dodgshon, R. A. 1975. ‘Scandinavian solskifte and the sun-wise division of land in Eastern Scotland’, Scottish Studies 19, 1–2 [1–24].

Dodgshon, R. A. 1987. ‘The landholding foundations of the open-field system’. In T. H. Aston (ed.) Landlords, Peasants and Politics in Medieval England. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 6–32.

Dodgshon, R. A. 1988. ‘The Scottish farming township as metaphor.’ In L. Leneman (ed.), Perspectives in Scottish Social History: Essays in Honour of Rosalind Mitchison. Aberdeen: Aberdeen University Press, 69–82.

Fleet, Chris. NLS Data Foundry, which explains how to download the GB1900 dataset and query it for names

Notes

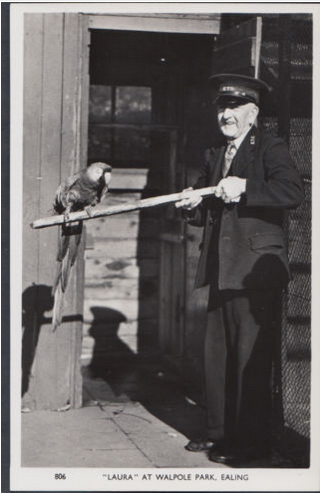

[1] My father went to school at Ealing Green, I used to visit the library next door and also the aviary with its parrot called Laura in the park behind (see below).

[2] Enid Blyton was a children’s author who wrote about a popular gnome called Big Ears. From about 1927 small gnome statues were sold as garden ornaments, forming part of British front-garden furniture.

[3] I’ve been unable to confirm if the householder was Wesleyan too but he’s buried in Nunhead’s Nonconformist chapel vault where he bought three loculi – or was buried, until cemetery neglect resulted in vandalism, and the redistribution of his and his two wives’ bones around the floor of the vault.

[4] East Auchenmade, although the alternative name ‘Sunnyside’ was restored on the 1910 Ordnance Survey map, so that it is now the name ‘East Auchenmade’ that is lost.

[5] As well as Ordnance Survey Name Books and ScotlandsPlaces, to find Sunnysides I scrutinised historic newspaper databases, old directories, the various websites for chasing one’s ancestors, the address-lists of historic societies, older maps, tax records, court records, borough registers …

[6] Ordnance Survey Name Book OS1/3/41/35: “The factor is of opinion that the proper way of spelling the name of this place is Auchen or Auchin Meade meaning (as he thinks) Stony Meadow” – Gaelic auchen was no longer transparent in 1856 when surveyed, but mead was meaningful to the inhabitants.

[7] the surname of a holder: “Mr. Love states that “Auchinmead Gemmill” is the name in the Title Deeds. “Hacks” is merely a popular designation; “Hacks” or “Hacks of Auchenmade” is the name by which it is known in the locality.” OS1/3/41/29.

Postcard of "Laura" parrot and bird keeper at Walpole Park, Ealing, published by Charles Skilton Ltd c. 1950s

Dr Laura Wright is a Reader in English Language at the University of Cambridge and co-Director of Cambridge Language Sciences (Michaelmas 2019). She is the author of Sunnyside: A Sociolinguistic History of British House Names (British Academy/OUP), 2020, which includes Middle English, Medieval Latin, Anglo-Norman French and Scottish Gaelic house names. Her most recent edited volumes are Herbert Schendl and Laura Wright (eds), 2011, Code-switching in Early English (Berlin: Mouton de Gruyter); Päivi Pahta, Janne Skaffari and Laura Wright (eds), 2017, Multilingual Practices in Language History: English and Beyond (Berlin: Mouton de Gruyter); and Laura Wright (ed.), 2020, The Multilingual Origins of Standard English. (Berlin: Mouton de Gruyter).

Title image: Sunnyside, Parish of New Cumnock, East Ayrshire, 1845, NS 56185 11252: Ayr Sheet XLI.15 (New Cumnock), survey date: 1857, publication date: 1860. Reproduced with the permission of the National Library of Scotland.